Hamnet is a slow, devastatingly beautiful film, directed by Chloé Zhao, whose sensitivity to interior lives and emotional landscapes is ideally suited to this eponymous book. Scored by Max Richter, the film approaches grief as a lived, interior condition. Richter’s music drifts between restraint and aching release, and the final scene feels very real. An unexpected surprise in recent cinema.

Adapted from Maggie O’Farrell’s novel, winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction and an international bestseller, the film retells Shakespeare’s life from an oblique, deeply human angle. Rather than centring literary genius, it focuses on the emotional cost that underpins it. At its heart is the death of Hamnet, Shakespeare’s eleven-year-old son, and the profound rupture this creates within a family. Grief is conveyed through small dislocations rather than dramatic declarations: silences, altered gestures, a marriage quietly reshaped by absence.

Although set in the late 16th century, Hamnet feels strikingly modern in its psychological outlook. The family at its centre lives at a remove from the rigid religious conventions of the time, seeking meaning instead through observation, imagination and care. Agnes, visionary, intuitive, and attuned to the natural world, educates her children through curiosity rather than doctrine. This emphasis on freedom, radical for its moment, allows both love and grief to be experienced without mediation, suggesting new ways of thinking about family and education that resonate strongly today.

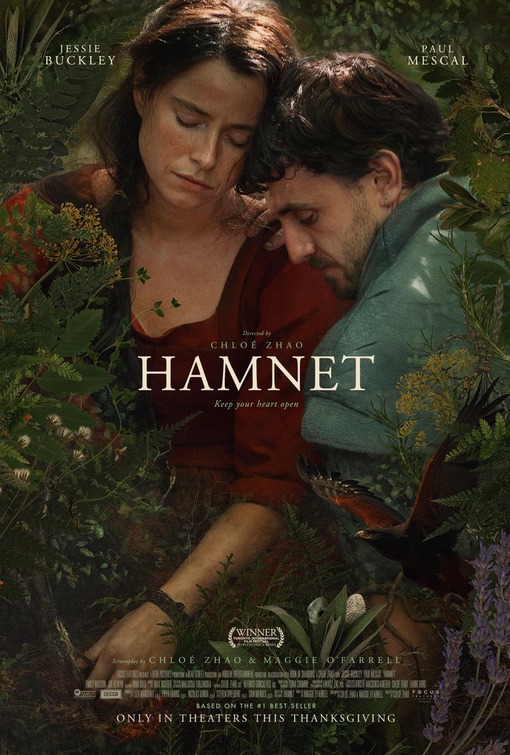

Zhao’s direction emphasises intimacy, allowing performances to unfold with quiet intensity. Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal, whose casting has drawn significant attention, anchor the film with remarkable emotional precision. Buckley’s Agnes is both grounded and otherworldly, while Mescal’s Shakespeare is rendered not as icon but as sensitive man, tender yet distant, loving (“He sees me for what I am” Agnes says at one stage to her kind brother) yet drawn away by work in London.

Richter’s score deepens this emotional terrain. His themes recur and shift, mirroring the non-linear rhythms of grief itself. Music becomes a psychological companion.

The film also gestures toward the generational dynamics that shape Shakespeare’s inner life. His own childhood is marked by harshness (Shakespeare was hired to be a Latin tutor to pay for his father’s debt), his father depicted as cruel, suggesting that emotional damage, brings kindness to the next generation. Against this backdrop, Shakespeare’s efforts to raise his children differently feel urgent and fragile. The freedom he seeks for them is not idealistic, but reparative.

In Hamnet, the plays hover at the margins – until the crucial crescendo final scene staged in Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Language matters, but so does what remains unsaid. The film proposes that Hamlet emerges not from ambition alone, but from the intimate devastation of loss. Art, poetry, language here, are a means of survival.

Ultimately, Hamnet depicts a family under pressure: how grief reorganises intimacy, how parents struggle to break cycles of damage, and how love persists. Under Zhao’s brilliant direction, and carried by Richter’s haunting score, the film feels profoundly contemporary. A must-see and a strong Award season contender.