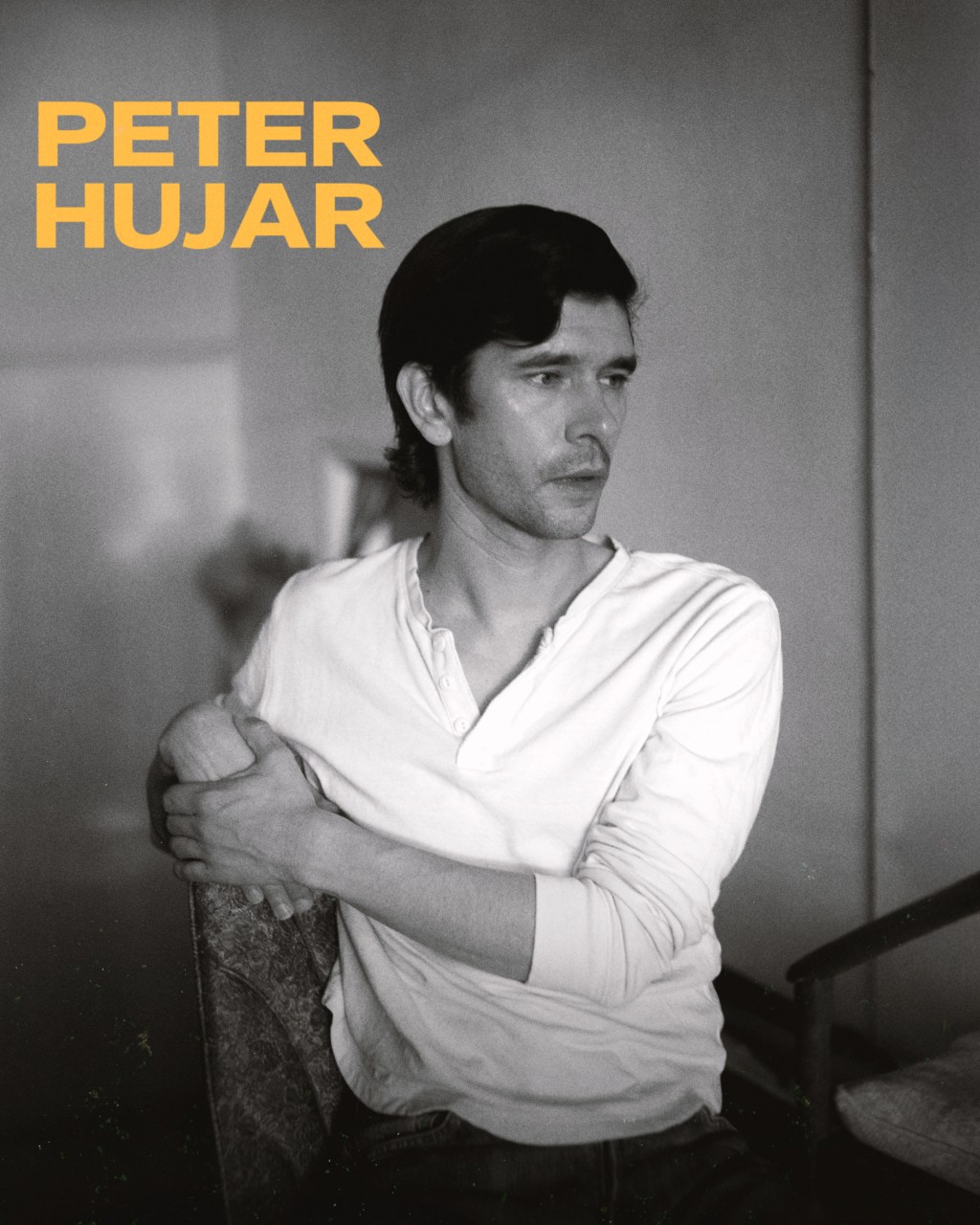

Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) is a 76-minute biographical drama directed by Ira Sachs and co-written with Linda Rosenkrantz, adapted almost entirely from the verbatim transcript of a conversation recorded in 1974.

Sachs’s film offers a quietly arresting portrait of the artist, drawn from a single conversation between Hujar and his close friend, the writer Linda Rosenkrantz. The exchange, originally intended for Rosenkrantz’s unrealised “day-in-the-life” project, documents Hujar recounting the minutiae of one winter’s day with exacting, often sardonic clarity: his meetings, his work, his meals, his moods. The film follows Eye Open in the Dark, a remarkable exhibition of the photographer’s work at Raven Row in London earlier in 2025.

“I wanted to be discussed in hushed tones. When people talk about me, I want them to be whispering.” Peter Hujar said himself and his quote is now certainly true with this fascinating film.

Though Hujar repeatedly claims that nothing of consequence occurred during this day, the account reveals an artist poised at an important, if understated, juncture in his life. Stylistically shot entirely in New York, the film situates this conversation against the city’s skyline, including a scene staged on the rooftop of the apartment, where the chaos presses into view.

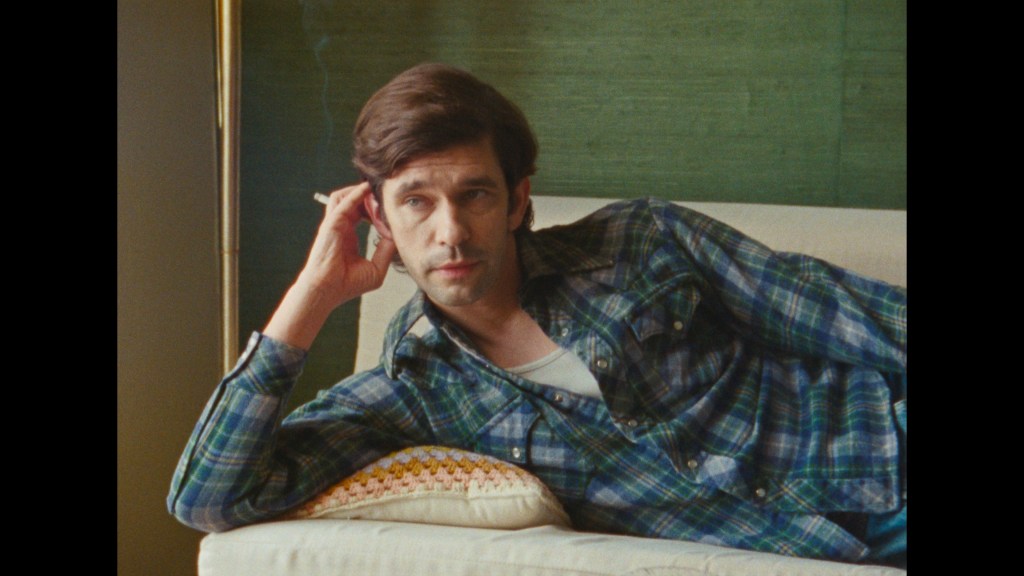

Sachs encountered the transcript decades later, in 2021, and was drawn as much to the intimacy of the exchange as to its content. Rather than staging a chronological reconstruction of Hujar’s day, he centres the film on the act of recollection itself. Ben Whishaw and Rebecca Hall inhabit Hujar and Rosenkrantz as two people bound by long familiarity, their intimate rapport unfolding across a sequence of domestic setting, living room, kitchen, bedroom, terrace, filmed on 16mm at Westbeth Artists Housing. Everyday actions punctuate the dialogue: a cigarette struck, food shared around the table, conversations in bed. These gestures lend the film a measured rhythm, while intermittent, carefully composed studio sequences gesture toward the formal intensity of Hujar’s photographic practice and the reciprocal nature of portraiture (that we don’t see at any point in the film).

Across the course of the conversation, a nuanced psychological portrait takes shape. Hujar emerges as precise, wry, generous, and restless, his warmth offset by moments of self-doubt and ambition. A fraught photo session with Allen Ginsberg, a call from Susan Sontag, and brief visits from friends drifting through his studio sketch the social and creative ecosystem in which he worked. Whishaw locates the dry humour embedded in Hujar’s speech, while Hall conveys Rosenkrantz’s attentiveness and understated care. The sparing use of Mozart’s Requiem heightens moments of stillness, lending the film a subdued, elegiac undertone.

The film’s approach echoes the qualities that define Hujar’s photography. His images are direct yet deeply sensitive, marked by an acute psychological awareness. He photographed artists, writers, queer figures, and members of New York’s underground with an unflinching openness, embracing male sexuality and confronting mortality without sentimentality. As Susan Sontag observed in her introduction to Portraits in Life and Death, Hujar understood that every portrait is also, inevitably, an image shaped by the presence of HIV-related death. A central figure in downtown New York during the 1970s and early 1980s, he produced work that granted dignity and gravity to lives often pushed to the margins. In this enclosed, conversational setting, both Whishaw and Hall deliver performances of remarkable restraint and depth, while Sachs continues his trajectory of emotionally attentive filmmaking, following great works such as Passages.

‘His desire for fame was based on a real lack. There’s something very moving to me about that, because he was very devoted to his art,’ Ben Whishaw said about Peter Hujar.

Hujar died in 1987 from AIDS-related pneumonia at the age of 53, having achieved only limited recognition during his lifetime, what has since been described as a form of “secret fame.” In the years following his death, his work has gained significant institutional and critical acknowledgement. Exhibitions have been mounted at Fotomuseum Winterthur, Kunsthalle Basel, the Grey Art Museum at NYU, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, and the Stedelijk Museum, which organised a retrospective in 1994. The touring exhibition Speed of Life (2017–2019), followed by solo presentations at FOMU Antwerp in 2021 and at the Istituto Santa Maria della Pietà as part of the 2024 Venice Biennale, further solidified his posthumous standing. His photographs now reside in the collections of major museums including the Art Institute of Chicago, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, SFMOMA, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

For Sachs, who has long felt a sense of kinship with Hujar and the East Village artists of his generation, the frankness of the transcript provides a rare point of access. Peter Hujar’s Day reconstructs a moment in time; it allows the viewer to encounter the artist as a working individual, uncertain, exacting, and quietly determined to change the course of art history on the verge of activism. “Anything that adds to Peter’s reputation as an important photographer gives me pleasure,” Rosenkrantz, who is still alive, writes in production material.

As Sachs has noted, the conversation reveals how difficult the act of making art can be. That recognition, that even Peter Hujar struggled, becomes one of the film’s most affecting revelations. Together, Sachs, Whishaw, and Hall create a quiet, time-capsule portrait that captures both the specificity of a moment and the interior life of an artist in reflection.

Shot on location in New York City, the film was produced by Jordan Drake Productions, ONE TWO Films, and Complementary Colors, and is a co-production between the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Spain. English-language throughout, the film was released theatrically in Germany on 6 November 2025, with subsequent releases in New York and Los Angeles, and is currently distributed internationally, including screenings at Picturehouse cinemas in the UK.

–

Thanks to Picturehouse